(Continuing from last week's posting)

I've long considered myself fortunate to have spent my formative years without television. First, it didn't exist. Then, buying a set was beyond our budget. And rather than having programmed images and stale interpretations set before our daughter (or us, for that matter), my husband and I chose to keep television out of our house, as well. We did not try to coerce her out of watching it at friends' houses. But we always felt there were more important things to do, even if that was sitting and gazing out a window.

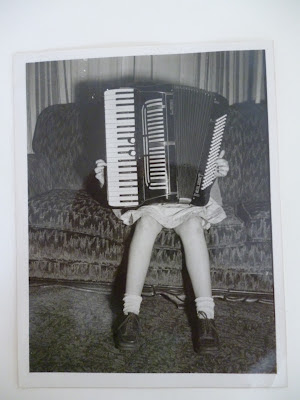

As children back in the '40s and '50s, my brother and I felt there was more to fill each day than there was time. Daydreaming reverie, of course, was still an honorable pastime. As well, we swam in a nearby creek with its yellow-green scummy boulders. We nibbled our rabbits' food-pellets from an open barrel in the garage. We played 78 RPM records or got out our John Thompson's First and Second Grade music books to practice the piano. My brother read the children's classics, many illustrated by N.C. Wyeth. I wrote poems and studied ballet with Madame Katrina who wore her hair up off the back of her neck. We went down to the wharf (we lived in Santa Barbara) and fished or roller-skated along the beach-walk. We played Robin Hood with bow and arrow, built forts in the bushes behind the house, or, butterfly net in hand, collected Lepidoptera. At one point, I rode my bicycle ten times around the block, no hands.

|

| Boy Scout sharpening his knife. |

That's how children grew up then. Until one day everything changed. For the society we were, what had seemed a cradle of boundless space became confined to half-hour segments. Where the experience of life itself had stirred us and helped make us wise, we were asked to hand over reality to a fictional substitute. What we had accepted as ours without price--ritual, play, celebration, fantasy, discussion, leisure--we gave away only to have it restructured and sold back to us. What had given little cause for concern became potential dark corners for real or imagined fear. Where we had celebrated function, we became addicted to dysfunction. What we had once mulled over, we were now asked to evaluate at flash-point speed so that we could accelerate our absorption of crises, enabling us to go on to the next and the next and the next, dulling our senses, disconnecting us from ourselves, exhausting our sweet, fragile selves into a weariness of boredom, isolation, cynicism, and malaise. When visiting relatives, we now sat in their darkened room watching stilted figures performing the raucous and slapstick.

Perhaps this disconnect/disconnection would enable us to re-connect later with a broader plug. But it's no state secret what appeared in the early '50s that changed us completely. Those of us born early enough to have escaped its brain-altering influence from the verbal to the visual and those of us financially disadvantaged enough never to have had it enter our house, surely have more in common with earlier generations than with the very one that followed ours.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment